Introduction

Perception and being active (i.e. having a certain level of motion freedom) are closely tied. Learning active perception and sensorimotor control in the physical world is cumbersome as existing algorithms are too slow to efficiently learn in real-time and robots are fragile and costly. This has given rise to learning in simulation which consequently casts a question on transferring to real-world. In this paper, we study learning perception for active agents in real-world, propose a virtual environment for this purpose, and demonstrate complex learned locomotion abilities. The primary characteristics of the learning environments, which transfer into the trained agents, are I) being from the real-world and reflecting its semantic complexity, II) having a mechanism to ensure no need to further domain adaptation prior to deployment of results in real-world, III) embodiment of the agent and making it subject to constraints of space and physics.

Publication

CVPR 2018.

[Spotlight Oral] [NVIDIA Pioneering Research Award]

F. Xia*, A. Zamir*, Z. He*, S. Sax, J. Malik, S. Savarese.

(*equal contribution)

[Paper] [Supplementary] [Code] [Bibtex] [Slides]

Spotlight Presentation

Platform Components

Real-world Complexity

Our images and models are sampled from real-world spaces (3D scanned), and offer 160% higher navigation complexity and 72.9% higher surface complexity compared to existing alternatives.

Physics & Optimization

Gibson integrates with Bullet3D physics engine and renders at a speed higher than real time. This enables training agents more efficiently inside our simulator than the physical world.

RL Ready

Gibson is RL ready and compatible with OpenAI gym. We provide sample code for training agents and pretrained results.

View Synthesis

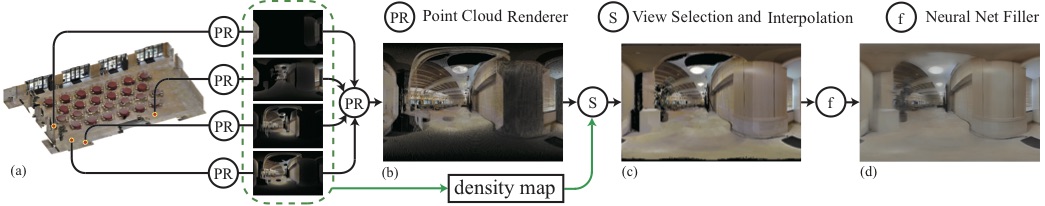

As our focus is on perception, it is important to provide agents with high-quality visual inputs. Our view synthesis module takes a set of point clouds and synthesizes a novel view from an arbitrary viewpoint.

Point Cloud Rendering

There are a number of major hurdles associated with using real-world scanning data. First, the scans locations are sparse, meaning that a certain extent of view interpolation is required. Second, the quality of depth image and 3D mesh outputs are limited to equipment and reconstruction algorithms, and often suffer from noticeable artifacts. Details such as vegetation and small objects cannot be properly reconstructed most of the time. Reflective surfaces, such as windows and countertops, will leave holes on the reconstructed mesh. All of these issues prevent us from using a rendering of meshes, or results of conventional Image Based Rendering pipelines, as our final RGB output. We instead adopt a two-stage approach, with the first stage being a purely geometric rendering from a point clouds. Our CUDA point cloud renderer can render 1024x2048 video streams with 10M points at 80fps. Details of our renderer can be found in the paper.

Neural Network Based Rendering

As mentioned above, a number of pathological artifacts common in fully geometric and image based rendering pipelines, such as stitching marks, lighting inconsistencies, and all issues caused by imperfections in the underlying mesh and RGBD scanner output, appear in our point cloud based rendering results. We use a neural network to alleviate these issues (e.g. fill in dis-occluded regions, remove geometric artifacts caused by errors in mesh, remove stitch marks) as well as baking in a domain adaptation mechanism named Goggles. The architecture and hyperparameters of our convolutional neural network filler are detailed in supplementary materials. There are a number of new key components incorporated in this part, including a stochastic identity initialization, a perceptual loss with hierarchical moment matching for color fidelity, and utilizing a fast bilinear interpolation. Details of our neural network filler architecture can be found in the paper and supplementary material.

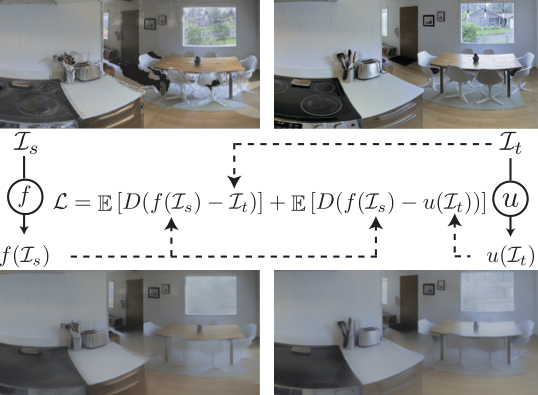

Transferring to Real-World: Goggles

We propose a novel domain adaptation mechanism, resembling corrective lense, which we refer to as goggles. We show that our goggle adaptation approach can effectively minimizes the gap between the synthesized and real world frames from the learner’s perspective

With all the imperfections in point cloud rendering, it has been proven difficult to get completely photo-realistic rendering with neural network fixes. The remaining issues make a domain gap between the synthesized and real images. Therefore, we formulate the rendering problem as forming a joint space ensuring a correspondence between rendered and real images, rather than trying to (unsuccessfuly) render images that are identical to real ones. This provides a deterministic pathway for traversing across these domains and hence undoing the gap. We add another network "u" for target image (I_t) and define the rendering loss to minimize the distance between f(I_s) and u(I_t), where "f" and "I_s" represent the filler neural network and point cloud rendering output, respectively (see the loss in above figure). We use the same network structure for f and u. The function u(I) is trained to alter the observation in real-world, I_t, to look like the corresponding I_s and consequently dissolve the gap. We named the u network goggles, as it resembles corrective lenses for the anget for deploymen in real world. Detailed formulation and discussion of the mechanism can be found in the paper.

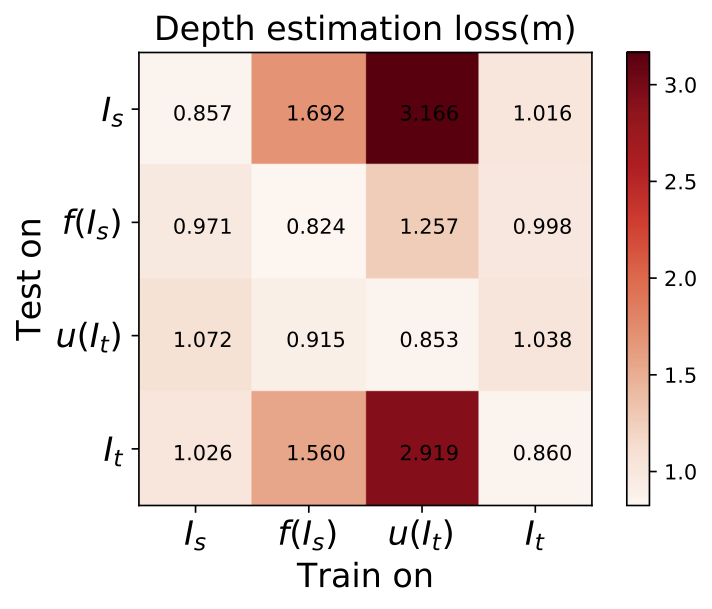

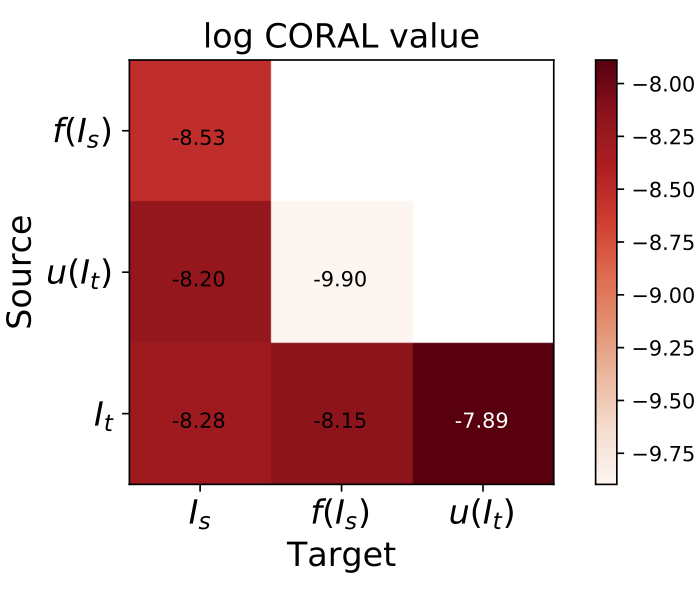

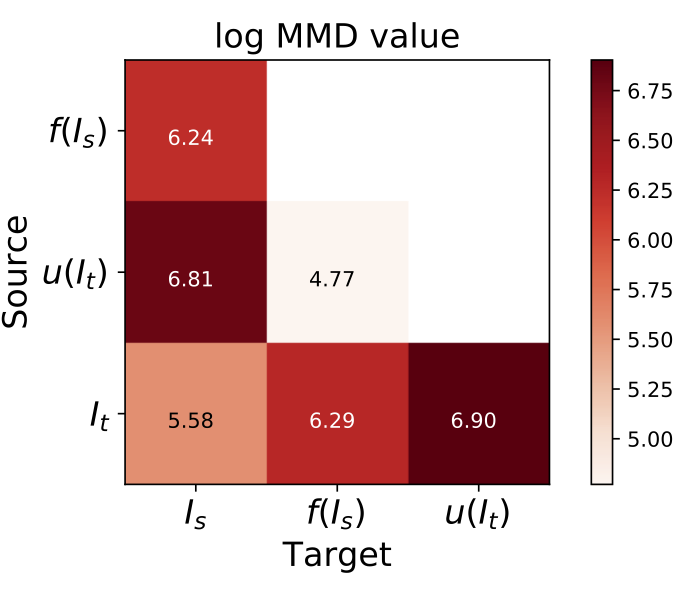

From Gibson to Real-World Perceptual Transfer Results

We evaluate our goggles mechanism on classical perception tasks (depth estimation and scene classification) as well as examined the distribution gaps on source and target images. We adopt two metrics MMD and CORAL, to test how well f(I_s) and u(I_t) domains are aligned. The detailed evaluations can be found in the paper.

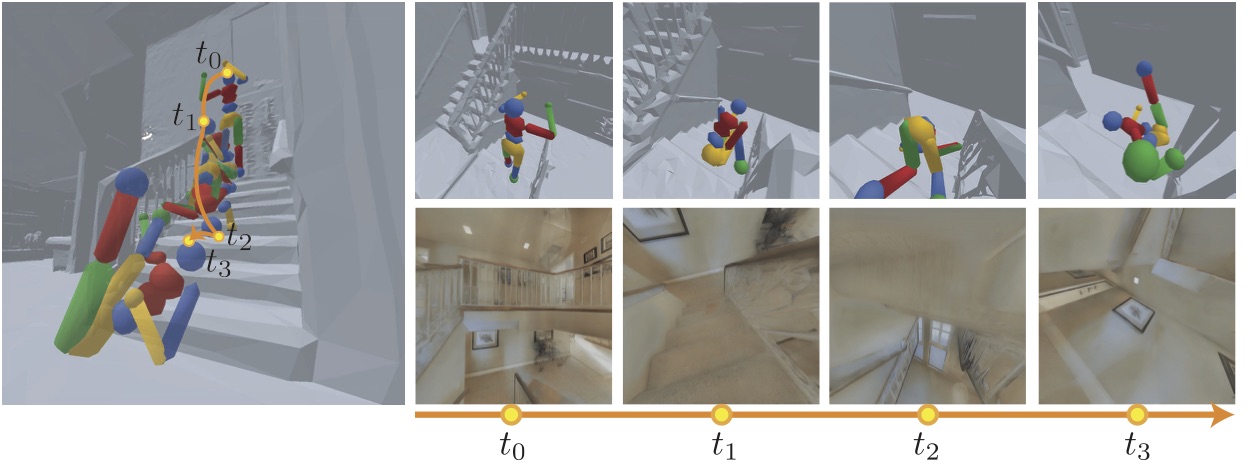

Physical Embodiment

The figure below shows a Mujoco humanoid model dropped onto a stairway demonstrating a physically plausible fall along with the corresponding visual observations by the humanoid's eyes.

To make the perceptual agents subject to constraints of physics and space, we integrate our environment with a physics engine. This allows us to expose our agents to physical phenomena such as collision, gravity, friction, etc. We base our physical simulator on Bullet Physics Engine, which supports rigid body and soft body simulation with discrete and continuous collision detection. Using GPU and OpenGL optimization, our environment supports learning physical interactions in 100x real-time speed. We also use Bullet Physics' built-in fast collision handling system to record each agent's interaction with the environment, such as how many times a collision happens. This allows us to compare different control algorithms in terms of their obstacle avoidance performance. Since scanned models do not come with material properties by default, our space do not offer realistic physical properties, such as material friction. We use Coulomb friction model by default within the physics engine to simulate that. To reduce computational complexity, we also do not model airflow in our physics engine unless activated by the user. Instead, we offer linear damping function for rigid body movements.

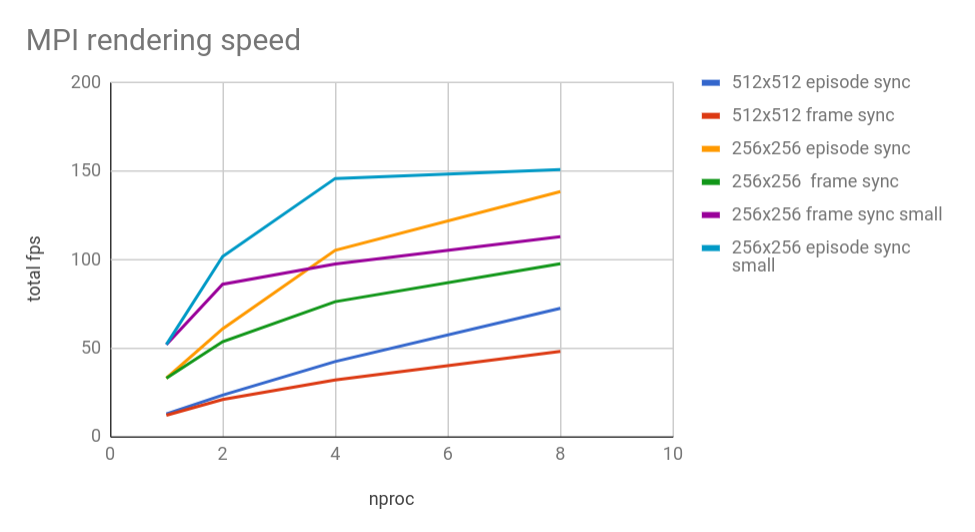

Optimized for Speed

Rendering speed is crucial for reinforcement learning. It is our guideline when building an environment to providevery high frame rate, such that we can simulate our envi-ronment at much faster speed than real time. We implemented our CUDA-optimized rendering pipeline for this purpose. We also offer different rendering resolutions, to account for different speed requirements.

Single Process. Tested on E5-2697 v4 + NVIDIA Tesla V100

| Resolution | 128x128 | 256x256 | 512x512 |

|---|---|---|---|

RGBD, pre networkf |

109.1 | 58.5 | 26.5 |

RGBD, post networkf |

77.7 | 30.6 | 14.5 |

RGBD, post small networkf |

87.4 | 40.5 | 21.2 |

| Depth only | 253.0 | 197.9 | 124.7 |

| Surface Normal only | 207.7 | 129.7 | 57.2 |

| Semantic only | 190.0 | 144.2 | 55.6 |

| Non-Visual Sensory | 396.1 | 396.1 | 396.1 |

We also tested on Intel I7 7700 + NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1070Ti and Intel I7 6580k + NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080Ti, the framerates are within 10% difference

Multi-process. Tested on E5-2697 v4 + NVIDIA Tesla V100

| Configuration | 512x512 episode sync | 512x512 frame sync | 256x256 episode sync | 256x256 frame sync | 128x128 episode sync | 128x128 frame sync |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 process | 12.8 | 12.02 | 32.98 | 32.98 | 52 | 52 |

| 2 processes | 23.4 | 20.9 | 60.89 | 53.63 | 86.1 | 101.8 |

| 4 processes | 42.4 | 31.97 | 105.26 | 76.23 | 97.6 | 145.9 |

| 8 processes | 72.5 | 48.1 | 138.5 | 97.72 | 113 | 151 |

Benchmarked for RGBD, post network code, which is the most computationally expensive.

Reinforcement Learning

The video shows some of the results of reinforcement learning policies trained in our environment. We choose (1) visual local planning and obstacle avoidance, (2) visual global planning and navigation, and (3) visuomotor control for complex locomotion as the three set of tasks we attempted.

Visual Local Planning

In this task we create an agent to do visual obstacle avoidance. The agent receives a continuous stream of Depth frames and decides where to move. We trained two husky agents with PPO algorithm for 150 episodes (300 iterations, 150k frames). The average reward over 10 iterations are plotted. The agent with perception achieves a higher score and developed obstacle avoidance behavior to reach the goal faster, compared to a non-visial agent with standard proprioception.

Visual Navigation

In this task, we set a fixed target B, and train the agent to go to B from an arbitrary and far location A with random initialization. The agent receives RGB only input without any external odometry or GPS target information. This has useful applications in robotics such as auto-docking. Global navigation behavior emerges after 1700 episodes (680k frames) training inside our environment. Compared with a baseline non-visual proprioceptual agent, whose input is its torque and wheel speed, the perceptual agent learns to navigate in complex environments, especially when there is randomization in its initial position. Furthermore, we do an active domain adaptation experiment using the trained policy and measure the policy discrepancy in terms of L2 distance of output logits across different domains. Our results (see paper) shows that the domain adaptation is effective when evaluated for an active task as well.

Complex Locomotion

In this task, we study the use of perception for the active agent in developing locomotion in complex environments. Locomotive agents trained with deep reinforcement learning are known to have difficulty generalizing to unseen environments and obstacles. We demonstrate that this difficulty can be reduced by adding perceptions. We train two ant agents to climb downstairs, using proprioception only (non-visual) state and proprioception-vision fusion state with depth camera input. We train both agents at fixed initial location, and observe that they start to acquire stair-climbing skills after 1700 episodes (700k time steps). The perceptual agent learns slower due to higher input dimension but has better generalizability as we test them with randomized initial location and different stairways. During test time, perceptual agents performs 70% better than sensor-only agent in terms of reaching the target location down the stairway.